Façade sociale - Solo show by EVOL : UN-SPACED Ephemeral Space - 18 Rue de l'Hôtel de Ville, 75004 Paris - Opening 17/02/2022

New ephemeral Space

---

FROM 17/02 - 13/03/2022

COME AND JOIN US

18 QUAI DE L'HOTEL DE VILLE

75004 PARIS - FR

Opening to the public from Wednesday to Saturday - 11 a.m. / 7 p.m.

or by appointment on others days

Nearest metro station:

Pont Marie – Cité Internationale des Arts

---

FROM 17/02 - 13/03/2022

COME AND JOIN US

18 QUAI DE L'HOTEL DE VILLE

75004 PARIS - FR

Opening to the public from Wednesday to Saturday - 11 a.m. / 7 p.m.

or by appointment on others days

Nearest metro station:

Pont Marie – Cité Internationale des Arts

-

EVOLFreudenberg (vor den Containern) (Freudenberg#3), 2021Sold

EVOLFreudenberg (vor den Containern) (Freudenberg#3), 2021Sold -

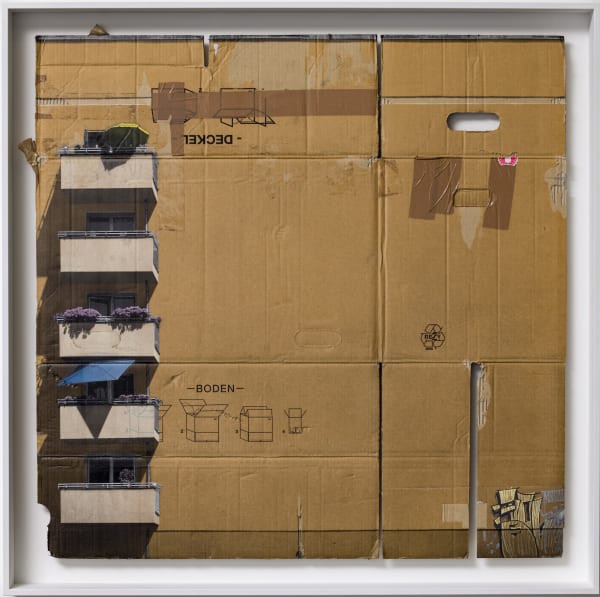

EVOLDeckel, gekippt. (RGBalconies #1), 2021Sold

EVOLDeckel, gekippt. (RGBalconies #1), 2021Sold -

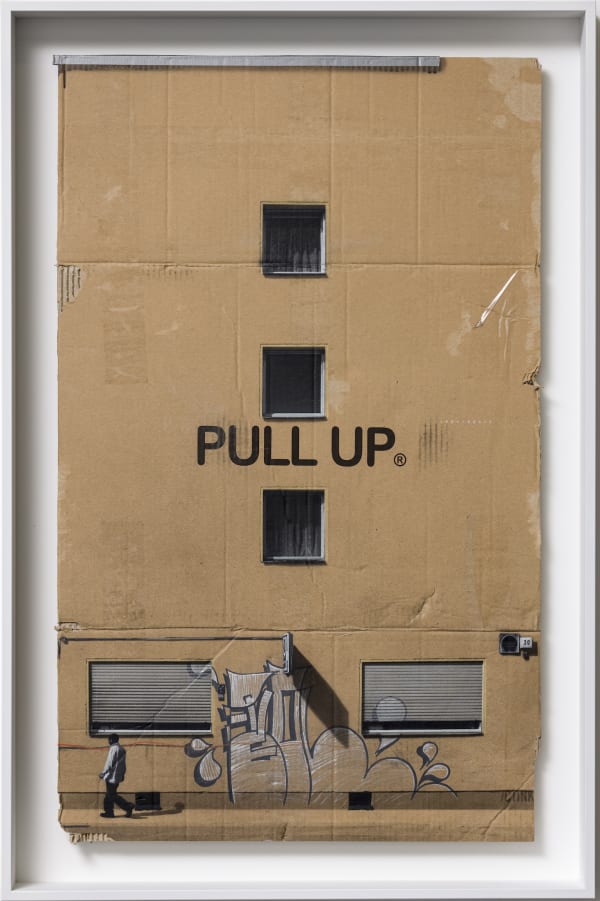

EVOL(pull up) (Sonnenallee #3), 2021Sold

EVOL(pull up) (Sonnenallee #3), 2021Sold -

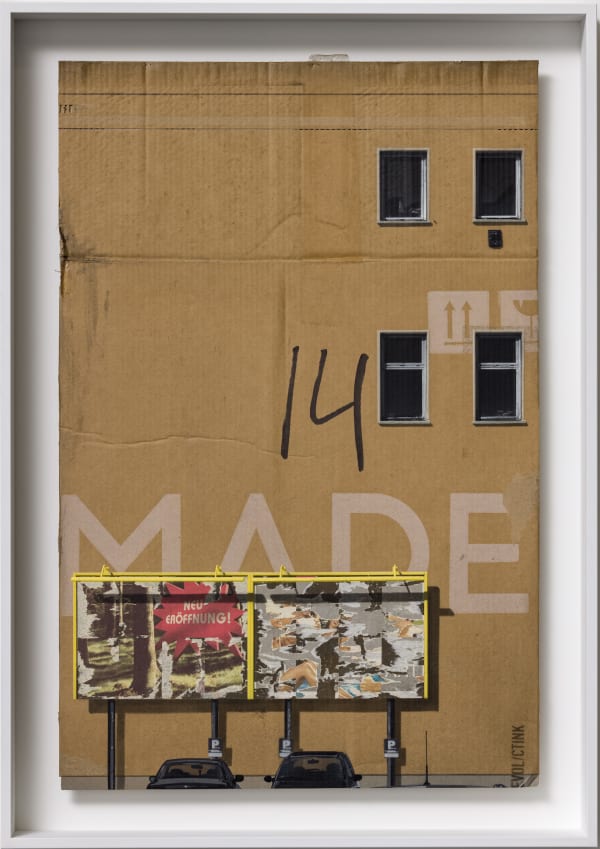

EVOLNeueröffnung (Werbetafeln#3), 2021Sold

EVOLNeueröffnung (Werbetafeln#3), 2021Sold -

EVOL“Alte Schule”, A.P, 2021Sold

EVOL“Alte Schule”, A.P, 2021Sold -

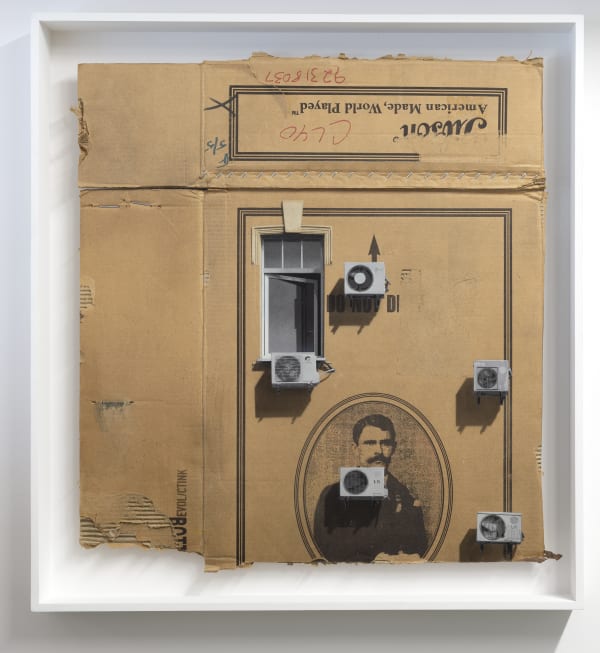

EVOLDo not D… (Just don’t do it), (Moscow Climate #2), 2022UniqueSold

EVOLDo not D… (Just don’t do it), (Moscow Climate #2), 2022UniqueSold -

EVOLHome sweet home (Vladivostok Vonders #2), 2022UniqueSold

EVOLHome sweet home (Vladivostok Vonders #2), 2022UniqueSold -

EVOLWhen in Warsaw... (Warsaw Blokk #2), 2022UniqueSold

EVOLWhen in Warsaw... (Warsaw Blokk #2), 2022UniqueSold -

EVOLHelsingforser Strass, AP, 2022UniqueSold

EVOLHelsingforser Strass, AP, 2022UniqueSold -

EVOLLarge Greens, 2017UniqueSold

EVOLLarge Greens, 2017UniqueSold -

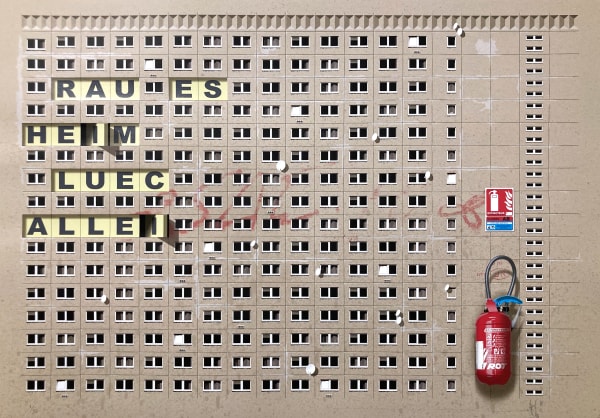

EVOLBlock Print BP05 (Wheel of Forune), 2022Limited edition of 120 + 5 AP + 3 PP€ 420.00

EVOLBlock Print BP05 (Wheel of Forune), 2022Limited edition of 120 + 5 AP + 3 PP€ 420.00

The living part of architecture

Tore Rinkveld aka Evol's first solo exhibition with the gallery Un-Spaced, Façade sociale brings together in the ephemeral space of the Cité des Arts in Paris a dozen works on cardboard. These are meticulous architectural views stenciled from photographs, most often in the artist's immediate environment in Berlin. They are the continuation of an approach initiated some fifteen years ago in the city, mainly on electrical cabinets where Tore Rinkveld applied himself to reproducing in small format the buildings of Friedrichshain, the district where he lives. These diversions have enabled him to impose his singularity: the creation of "meta-architectural" works that are, by his own admission, reflections of our societies.

Before him, few artists creating in the urban space had criticized architecture in the very place where it was deployed. Graffiti writing must undoubtedly be seen as an impulse of this kind, but this indiscipline is far too abundant to impose such a univocal reading. It is rather in conceptual art that one must look for related approaches, without them being direct sources of inspiration for the artist. In his in situ works, there is something of the striped bands with which Daniel Buren underlines the characteristics of a place, and of course of the "anarchitect" Gordon Matta-Clark, whose questioning of the urban dynamics specific to the metropolises of the 1970s leads to an intervention in the very structure of the building. Like them, Tore Rinkveld gives the spaces he invests their own reflection. This is his way of evoking their history and future without falling into the trap of overly explicit discourse. This discreet intention is also reflected in his works on cardboard. For example, to present the works in the exhibition Façade sociale, he chose a raw space with textured walls, in the image of those he likes to represent.

In his work, however, the critique of architecture in action is expressed in a realistic rather than conceptual vein. In his studio works, a gutter, an electric wire, a reflection on a window, a curtain or a potted plant complete the illusion of a living space. Thus, his façades are the result of a complex work of deconstruction of the image. To produce them, Evol creates a large number of layers on the computer, sometimes up to thirty. From the photographs that serve as preparatory documents, he extracts a detail, isolates it and rearranges it to make it stand out in the final composition. In order to draw attention to the architecture and what it says about society, he relies on the purity and accuracy of the representation.

This precision, which denotes a rare mastery of the stencil, evokes at first sight architectural drawing. The frontal character of the buildings patiently assembled by the artist first recalls the elevations: these technical drawings are intended to represent the façade of a building to be constructed, most often with the aim of giving a precise idea of it to the client. The presence of a passer-by, graffiti, an antenna or a satellite dish, in short anything that signals the idea of an animated space, also places Evol's works in the tradition of vedute. Very much in vogue in the 18th century, these urban views inherited architectural drawing but emancipated themselves from its technical vocation: they were made for contemplation, and no longer to guide the design of a building.

This is why the masters of the genre use the camera oscura, which enables them to arouse admiration through their perspective effects and their play of light and shadow. The same applies to the façades created by Tore Rinkveld: while apparently subscribing to the conventions of the elevations, they differ from them in their ambition to make people see and, above all, think.

In this case, their realism and precision make it possible to bring back to the human scale an urbanism that exceeds it in principle: functionalism. Implemented after the war in all Western metropolises, and particularly in East Berlin under Soviet control, this model of development is characterised by its planning. It was no longer designed at the level of the

human being, but from above, by professionals concerned above all with regulating flows and disciplining people. By miniaturising the buildings created by the reconstruction, Tore Rinkveld takes the exact opposite view of the urban planners. He brings their cold creations back to the right and only scale: that of the local resident, the inhabitant, the stroller, in short, the human being who lives or passes by. He talks about portraits of the buildings he paints in situ or in the studio. It is the lived space that interests him, in preference to the designed space. More than a reference to the social housing that is omnipresent in his work, the title of the exhibition Social Facade should probably be read in this sense: every facade is social by definition, because architecture produces uses at least as much as concrete. It is not simply a shelter or an envelope to protect oneself from the cold and rain, but a place of life.

Hence Evol's interest in cardboard. The cardboard he uses is like the buildings painted on it. Covered with brown tape, small tears, handwritings or prints, they have lived and bear the traces of their past uses. The artist takes care to reconstruct their history, writing on the back of each one the place where it was collected. Even more ephemeral than a human life, they also have something cheap and negligible about them, like the working classes of Friedrichshain, which are recycled elsewhere to make way for high-end real estate developments and furnished accommodation for tourists. Their fragility thus supports a form of nostalgia in Evol's work: it doubles as a meditation, basically romantic, on the future of a Berlin in the process of gentrification.

Finally, like the architecture, the cardboard is stretched between the interior and the exterior: made to protect its contents, it is only worthwhile for this function. In the artist's works, it is reduced to its almost flatness, and therefore unfit for use, allowing him to better highlight the relief of living spaces, their particular vibrancy, their personality. The signs and inscriptions printed on it become elements of the urban décor, winks to the political and cultural context. They blend in with the architectural drawing to discreetly distil effects of presence in the image. Through a subtle play of echoes, they engage in a lively conversation with passers-by, with the graffiti, with the architectural elements.

This conversation, it must be said, goes far beyond the criticism of a dehumanising urbanism. It also involves play and counterpoint. By reversing the uses, forms and functions of cardboard and architecture, by mixing urban signs and printed signs, Evol is having fun. He had even more fun when, on the occasion of Façade sociale, he printed a silk-screen of his Wheel of fortune intervention in 2014 at the Palais de Tokyo. Of this one, he proposes a mise en abyme version, which makes the most of what is around the work. A fire extinguisher or a label become prominent elements, as if to better underline the gap between a coveted contemporary art space and the dreary concrete buildings that are painted on it.

The throw-ups and graffiti that the artist distils in some of these pieces also manifest this art of counterpoint in their own way. Of course, they contribute to the effect of reality of his façades, since they assert themselves here as the banal elements of any urban environment. But they also superimpose a temporal scale on the spatial scale, creating a shortcut between Evol's past as a graffiti artist and his contemporary work. Above all, they bring back a bit of singularity to a setting that is being dispossessed. Thanks to them, the artist describes in filigree a city in his image, appropriable, habitable, offered to exploration and to the I(u). Like a final pied-de-nez to all planners and developers.